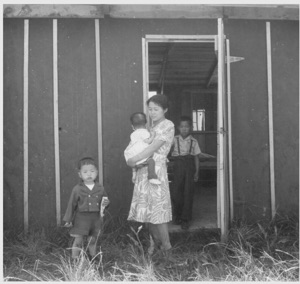

Photo credits: Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives and Densho

A few months after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which indelibly changed the lives of Japanese and Japanese Americans living on the West Coast.

120,000 Japanese immigrants and those of Japanese descent were forcibly removed from their homes and put into isolated camps away from their communities and livelihoods. Two thirds of those incarcerated were American citizens. The reasons the government gave as its rationale was the security of the United States against Japan and also the “protection” of the mainland Japanese against retribution for the bombing. These were both later proved false by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in the 1980s. Not one Japanese national or Japanese American was ever found guilty of sabotage or espionage.

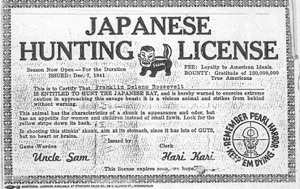

The underlying reasons for the incarceration were long standing and involved widespread racism, an atmosphere of hysteria, industries such as agriculture and fisheries threatened by the success of Japanese American businesses, and newspapers such as those owned by William Randolph Hearst drumming up fear and scare tactics.

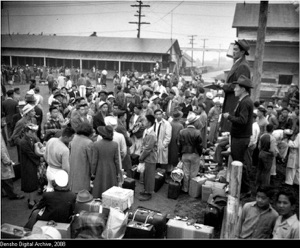

Orders to immediately leave their homes gave the Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans little time to prepare, and billions of losses were incurred as they hastily sold their goods at bargain prices, lost what they couldn’t sell, and gave up thriving businesses up and down the west coast. They could take only what they could carry.

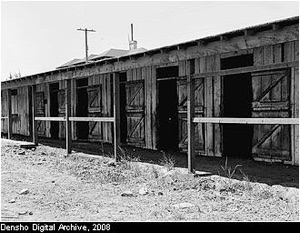

The conditions of the temporary detention camps were deplorable: often former horse and animal stalls in race tracks and fairgrounds with open partitions between family units and unsealed outer walls that let in wind, cold and dust. Families were made to share one small room and sometimes had to share the space with non-related individuals. There was no privacy, as the partitions between units were open at the top, and noise traveled all the way down the barracks. Many of the restroom facilities were unsanitary and overcrowded. Lines were everywhere, for the mess hall, for the bathrooms, for the laundry.

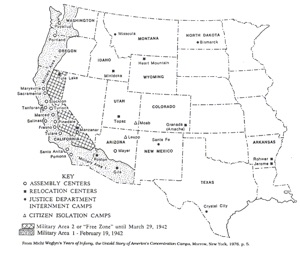

The 10 permanent detention camps were situated in isolated areas inland, with harsh weather conditions: freezing cold in the winter, and unbearably hot in the summer. Dust storms were common. The mess halls that served food foreign to the Japanese American diet also broke up the traditional family dynamic, as young adults chose to eat together and away from their families.

But the Japanese Americans strove to make their new communities as comfortable as possible, rebuilding their living spaces with scrap lumber, fashioning crafts and objects of beauty out of what they could find on the grounds, and creating clubs and physical activities that would improve their lives.

One such activity were the big bands and swing bands that cropped up simultaneously in all of the camps and were embraced by the younger second generation, the Nisei, Japanese Americans. The positive release that the bands generated is also a lasting legacy with those Japanese Americans who played or sang in the bands, and also with many who were able to attend the dances.

livepage.apple.com